- India

- International

Why the world’s in a second race to the moon

Fifty years after Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin created history, and, on the eve of India’s second lunar mission – Chandrayaan 2 – let's take a look at man’s oldest muse and how it has inspired all manner of human endeavour. First up, why a renewed surge of interest in moon travel is both an indication of the complexities of lunar missions and a future foretold.

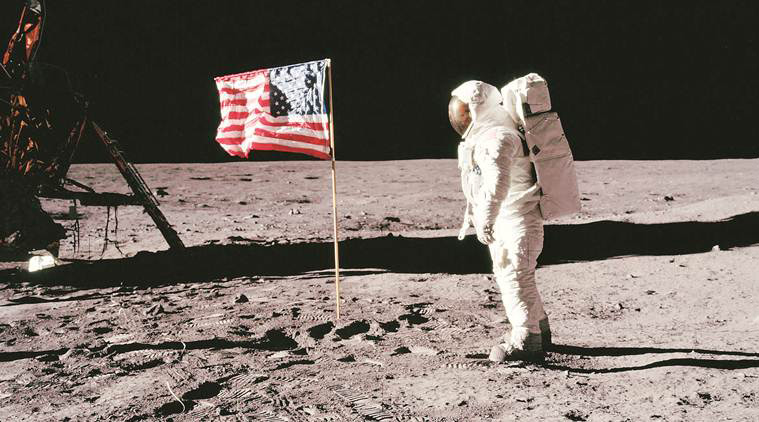

Making history: Neil Armstrong on the moon in 1969. (Photo: NASA)

Making history: Neil Armstrong on the moon in 1969. (Photo: NASA)

“I am quite certain that we will have such bases (on the moon) in our lifetime… somewhat like the Antarctic stations… continually manned,” Neil Armstrong said in 1970, in response to a question in a BBC interview on whether he thought it was possible to set up scientific bases on the moon in the forseeable future.

Armstrong, the first man to set foot on the moon, went on to live for another 42 years. Far from creating permanent scientific facilities in that time, human beings, it appeared, actually withdrew from the moon. Consider this: in the decade between 1965 and 1975, the United States and the then USSR, the only two countries with space programmes at the time, sent more than two dozen lunar probes. These included NASA’s Apollo missions, six of which landed a total of 12 astronauts on the surface of the moon between 1969 and 1972. Curiously, however, for the next almost two decades, there was not a single lunar mission launched by any space agency. Human beings seemed to have suddenly lost interest in the moon. And, when the lunar exploration did resume in 1994, it did not begin from where the scientists had left off in the mid-1970s, but, seemingly, almost from scratch, by sending orbiters, landers and rovers. Just two missions were launched in the 1990s and another six in the next decade by which time, other players like India, China and Japan had also entered the fray.

Follow Chandrayaan-2 launch LIVE updates

The last decade has seen a renewed interest in the moon, especially after the discovery of water on the lunar surface by Chandrayaan-1 mission in 2008. But it is only now, 50 years from the first landing on July 20, 1969, that humans have finally decided to go back to the moon. Last year, NASA had announced that it planned to send a manned mission to moon by the year 2028. In April this year, the US administration asked NASA to do this by 2024 itself. Most likely, by that time, some other countries, India and China among them, would be competing to send their own human missions to the moon.

The stage is now set again for a race to the moon over the next decade, and, this time, it is likely to be markedly different from the earlier one. In all probability, it will involve multiple participants, be more collaborative than competitive, and will be guided by the overall objective of utilising the resources of the moon, setting up permanent facilities for scientific explorations and using it as a launch pad to take humans deeper into space — the kind of things that Armstrong was talking about in the 1970 interview.

It is remarkable that it has taken 50 years for human beings to plan their journey back to the moon, to do the kind of things that many believed was just an arm’s length away in the 1970s itself. Half a century is a pretty long time for any new technology to mature and get adopted for common use. It is hard to think of any other breakthrough 20th century technology that would have remained stagnant for this long. This is, of course, not to suggest that space exploration hasn’t progressed in the last 50 years. Far from it. Spacecrafts have now gone beyond the solar system, exploratory missions have probed Mars, Jupiter and Saturn, more than 500 astronauts have travelled to space and come back, and scientists have built a massive permanent laboratory in space, the International Space Station (ISS), that has been manned continuously for almost two decades now.

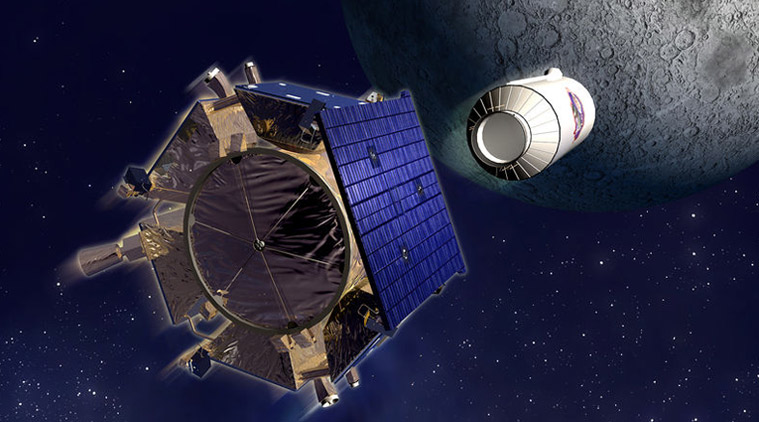

An artist’s rendering of the LCROSS (the lunar crater observation and sensing satellite) spacecraft and Centaur separation. (Photo: NASA)

An artist’s rendering of the LCROSS (the lunar crater observation and sensing satellite) spacecraft and Centaur separation. (Photo: NASA)

Yet, the main excitement of space exploration emanates from the promise it brings of transporting humans to new worlds — the possibility of travelling deep into space, of landing, and living, on other planets, of encountering aliens.

Read | Destination Moon: Chandrayaan-2 to launch India into new space age

Going to the moon is just the first step in this endeavour. And strangely, we have been stuck at this first step for 50 years now.

A Premature Achievement

By all accounts, the 1969 landing of the Apollo-11 mission, which saw Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin set foot on the moon for the first time, came a bit prematurely in the space age. It had been barely 12 years since the first-ever satellite, Sputnik, had been launched into space, marking the beginning of the space era. The landing was premature because the technology ecosystem that could have maximised the benefits of a scientific breakthrough as big as this was still to be built, and hence, once man reached the moon, they did not know what more to do.

But those Apollo missions to the moon were hardly guided by science objectives. They were driven mainly by geo-political and nationalistic considerations. Mylswamy Annadurai, mission director, Chandrayaan-1, India’s first lunar probe, describes them as “adventure missions” considering the high degree of risk they entailed.

At the peak of the Cold War (1962-1979), the then USSR seemed to have taken a decisive lead over the United States in the most glamorous technology till date, having sent the first satellite in space, the first spacecraft to crash on to moon’s surface, and the first astronaut in space, all in a matter of four years between 1957 and 1961. The US had to do something really dramatic to establish its supremacy. The result was President John F Kennedy’s famous May 25, 1961 speech declaring the country’s intention to put a man on moon before the end of the decade.

For the next few years, the US directed all its resources towards this objective. NASA accounted for as much as 4 per cent of the entire federal budget in 1965. In comparison, in the past few decades, when its scale of operations has grown manifold, NASA’s budget has always been below 1 per cent of the federal budget. Scientists also built the most powerful rocket ever, the Saturn-V, to take the spacecraft to moon. “The Apollo landing so early in our space age was, no doubt, an outcome of Cold War rivalry. It was all about seeking dominance in space. Resources were mobilised on a war-scale. But it doesn’t take away anything from the heroic achievement. There was huge amount of scientific information that came out of those missions. The rocks and other samples that the astronauts returned with were a wealth of information,” says Anil Bhardwaj, director of Ahmedabad-based Physical Research Laboratory.

One after the other, NASA landed six Apollo spacecraft on the moon, each carrying two astronauts with it, before abandoning the extremely expensive programme in 1972. Beaten in the race, the USSR, which was preparing feverishly to take a man to the moon, too, lost interest in just emulating the US and dropped its plans.

All information about the moon at that time, gleaned from the rock samples brought back by the astronauts, as well as from other studies, pointed to moon having a bone-dry surface, bereft of any water. If human beings had to build a permanent scientific station on the moon, they would have to carry not just all their material from the earth, but also water. “This would be prohibitively costly and would severely restrict our proposed activities on the moon. The ability to go to the moon had been successfully demonstrated. There was no point in repeating it. Subsequent travel to the moon had to be scientifically meaningful and economically justifiable in the absence of a strong emotional reason that the Cold War presented,” Bhardwaj says.

An image combined from separate images of the Earth and the moon, taken by the Galileo spacecraft in 1992. (Photo: NASA/JPL/USUGS)

An image combined from separate images of the Earth and the moon, taken by the Galileo spacecraft in 1992. (Photo: NASA/JPL/USUGS)

Besides, the Apollo missions were also extremely risky. “Today’s safety norms would just not allow anything like that to be launched. The risks were just too great,” says Annadurai. Armstrong himself has been quoted as saying that he believed there was only a 50 per cent chance of his mission being successful. With the US supremacy in space having been established, and little scientific reasoning to justify the exorbitant manned missions, the journeys to moon were halted.

Confirmation of Water

The scientists’s perception of the moon changed considerably once traces of water molecules were discovered. To be sure, the possibility of finding water on the moon’s surface was being talked about since the 1970s, but the evidence was weak. In the 1990s, both the Clementine and the Lunar Prospector, the two NASA missions that restarted lunar exploration, picked up signals of water on moon. So did the Cassini mission in 1998, which flew by the moon on its way to Saturn.

Read | The biggest challenge for Chandrayaan-2: Surviving days and nights on the moon

But the conclusive evidence of the presence of water on the moon was delivered by two instruments on board Chandrayaan-1 — the Moon Mineralogy Mapper placed by NASA, and ISRO’s own Moon Impact Probe that was made to crash on the moon’s surface. This was reconfirmed by the instruments on Lunar Reconnissance Orbiter mission, launched by NASA a year after Chandrayaan-1. “The discovery of water changes everything. It gives rise to a host of possibilities. It is this discovery of water that has triggered all the space faring nations to start looking at moon again,” Annadurai says.

In addition to the sustenance of life, water could also be utilised as a fuel to power rockets for deep interplanetary missions. “Water can be broken into hydrogen and hydroxide molecules. Hydrogen can be used for power generation as well as a propellant to in rockets. In the long run, if we are to use moon as a launch pad for going further into space, then we would need to develop technologies to extract hydrogen from the water on the moon and use it as a fuel,” Bhardwaj says.

So far, water on the moon has not been found in liquid form. Instead, H2O molecules have been observed in some rock layers, trapped as ice. In fact, the analysis of data produced by recent lunar missions suggest that significant amount of water, in ice form, may be present on the moon, especially in the polar regions, which has large craters, some of them extending to several thousands of kilometres in size. The craters are believed to hold large amounts of ice.

Read | The brave new world to expect with the new race to the moon

This has triggered a new-found interest in exploring the polar regions of the moon. So far, all the landings on the moon have happened near the moon’s equator. This is because this area receives maximum amount of sunlight, essential to keep the solar-powered instruments running. For the first time, the Chandrayaan-2 mission, India’s second lunar probe that would be launched tomorrow morning, would land in the polar region, and would try to assess the amount of water present there, apart from studying its topography.

Mission Possible

Discovery of water, though the most critical, is not the only thing that has rekindled interest in the moon. “We have technologies that now make it possible to build in-situ, on the surface of the moon, using materials found there. We have 3-D printing technologies to achieve this. It is also very much in the realm of possibility to extract and use hydrogen as an energy source, or even the Helium-3 which is abundantly available on the moon, as a source of immense energy in nuclear fusion reactors. Of course, not all of it would be possible the first time we go back there. But we are now in a position to realistically plan for these things, so that in the long term we have a permanently habitable station on the moon,” Annadurai says.

An extremely likely scenario, that is actively under consideration, is to create a permanent space station, like the ISS, on the surface of the moon in the next 10 years. The ISS, that serves as a permanent laboratory in space, about 400 km above the earth’s surface, is due to retire latest by 2028, and no replacement for it has been decided as yet.

“An international lunar space station is on the cards. I think teams from nearly 10 countries are already working on that idea. India is part of that. It is quite a doable idea. The budget would be huge but the support for it is much more broad based than the ISS which is a NASA facility and has been used only by Americans and Russians,” he says.

This article appeared in the print edition with the headline ‘ Flag on the Moon’

Apr 23: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05